N E W M E D I A A R T . E U

> Paris Photo

> Art, technology and AI

> Immersive Art

> Chroniques Biennial

> 7th Elektra Biennial

> 60th Venice Biennial

> Endless Variations

> Multitude & Singularity

> Another perspective

> The Fusion of Possibilities

> Persistence & Exploration

> Image 3.0

> BioMedia

> 59th Venice Biennale

> Decision Making

> Intelligence in art

> Ars Electronica 2021

> Art & NFT

> Metamorphosis

> An atypical year

> Real Feelings

> Signal - Espace(s) Réciproque(s)

> On Combinations at Work

> Human Learning

> Attitudes and forms by women

> Ars Electronica 2019

> 58th Venice Biennale

> Art, Technology and Trends

> Art in Brussels

> Plurality Of Digital Practices

> The Chroniques biennial

> Ars Electronica 2018

> Montreal BIAN 2018

> Art In The Age Of The Internet

> Art Brussels 2018

> At ZKM in Karlsruhe

> Lyon Biennale 2017

> Ars Electronica 2017

> Digital Media at Fresnoy

> Art Basel 2017

> 57th Venice Biennial

> Art Brussels 2017

> Ars Electronica, bits and atoms

> The BIAN Montreal: Automata

> Japan, art and innovation

> Electronic Superhighway

> Lyon Biennale 2015

> Ars Electronica 2015

> Art Basel 2015

> The WRO Biennale

> The 56th Venice Biennale

> TodaysArt, The Hague, 2014

> Ars Electronica 2014

> Basel - Digital in Art

> The BIAN Montreal: Physical/ity

> Berlin, festivals and galleries

> Unpainted Munich

> Lyon biennial and then

> Ars Electronica, Total Recall

> The 55th Venice Biennale

> The Elektra Festival of Montreal

> Digital practices of contemporary art

> Berlin, arts technologies and events

> Sound Art @ ZKM, MAC & 104

> Ars Electronica 2012

> Panorama, the fourteenth

> International Digital Arts Biennial

> ZKM, Transmediale, Ikeda and Bartholl

> The Gaîté Lyrique - a year already

> TodaysArt, Almost Cinema and STRP

> The Ars Electronica Festival in Linz

> 54th Venice Biennial

> Elektra, Montreal, 2011

> Pixelache, Helsinki, 2011

> Transmediale, Berlin, 2011

> The STRP festival of Eindhoven

> Ars Electronica repairs the world

> Festivals in the Île-de-France

> Trends in Art Today

> Emerging artistic practices

> The Angel of History

> The Lyon Biennial

> Ars Electronica, Human Nature

> The Venice Biennial

> Nemo & Co

> From Karlsruhe to Berlin

> Media Art in London

> Youniverse, the Seville Biennial

> Ars Electronica, a new cultural economy

> Social Networks and Sonic Practices

> Skin, Media and Interfaces

> Sparks, Pixels and Festivals

> Digital Art in Belgium

> Image Territories, The Fresnoy

> Ars Electronica, goodbye privacy

> Digital Art in Montreal

> Art, technology and AI

> Immersive Art

> Chroniques Biennial

> 7th Elektra Biennial

> 60th Venice Biennial

> Endless Variations

> Multitude & Singularity

> Another perspective

> The Fusion of Possibilities

> Persistence & Exploration

> Image 3.0

> BioMedia

> 59th Venice Biennale

> Decision Making

> Intelligence in art

> Ars Electronica 2021

> Art & NFT

> Metamorphosis

> An atypical year

> Real Feelings

> Signal - Espace(s) Réciproque(s)

> On Combinations at Work

> Human Learning

> Attitudes and forms by women

> Ars Electronica 2019

> 58th Venice Biennale

> Art, Technology and Trends

> Art in Brussels

> Plurality Of Digital Practices

> The Chroniques biennial

> Ars Electronica 2018

> Montreal BIAN 2018

> Art In The Age Of The Internet

> Art Brussels 2018

> At ZKM in Karlsruhe

> Lyon Biennale 2017

> Ars Electronica 2017

> Digital Media at Fresnoy

> Art Basel 2017

> 57th Venice Biennial

> Art Brussels 2017

> Ars Electronica, bits and atoms

> The BIAN Montreal: Automata

> Japan, art and innovation

> Electronic Superhighway

> Lyon Biennale 2015

> Ars Electronica 2015

> Art Basel 2015

> The WRO Biennale

> The 56th Venice Biennale

> TodaysArt, The Hague, 2014

> Ars Electronica 2014

> Basel - Digital in Art

> The BIAN Montreal: Physical/ity

> Berlin, festivals and galleries

> Unpainted Munich

> Lyon biennial and then

> Ars Electronica, Total Recall

> The 55th Venice Biennale

> The Elektra Festival of Montreal

> Digital practices of contemporary art

> Berlin, arts technologies and events

> Sound Art @ ZKM, MAC & 104

> Ars Electronica 2012

> Panorama, the fourteenth

> International Digital Arts Biennial

> ZKM, Transmediale, Ikeda and Bartholl

> The Gaîté Lyrique - a year already

> TodaysArt, Almost Cinema and STRP

> The Ars Electronica Festival in Linz

> 54th Venice Biennial

> Elektra, Montreal, 2011

> Pixelache, Helsinki, 2011

> Transmediale, Berlin, 2011

> The STRP festival of Eindhoven

> Ars Electronica repairs the world

> Festivals in the Île-de-France

> Trends in Art Today

> Emerging artistic practices

> The Angel of History

> The Lyon Biennial

> Ars Electronica, Human Nature

> The Venice Biennial

> Nemo & Co

> From Karlsruhe to Berlin

> Media Art in London

> Youniverse, the Seville Biennial

> Ars Electronica, a new cultural economy

> Social Networks and Sonic Practices

> Skin, Media and Interfaces

> Sparks, Pixels and Festivals

> Digital Art in Belgium

> Image Territories, The Fresnoy

> Ars Electronica, goodbye privacy

> Digital Art in Montreal

> >

THE STRP FESTIVAL OF EINDHOVEN

by Dominique Moulon [ January 2011 ]

The fourth edition of the STRP festival, which is devoted to bringing together music and artistic and technological practices, drew more than 30,000 visitors to its many concerts, performances, exhibitions, conferences and workshops in November 2010. As for the rather strange name for the event, it relates to the industrial site of Eindhoven that used to house the Philips brand before it revolutionised the cultural industry with its inventions.

Marnix de Nijs

"Physiognomic Scrutinizer",

2008-2009.

Zilvinas Kempinas

"Double O", 2008.

Lawrence Malstaf,

"Nevel", 2004,

Courtesy Fortlaan 17 Gallery.

Lawrence Malstaf,

"Boreas", 2007,

Courtesy Fortlaan 17 Gallery.

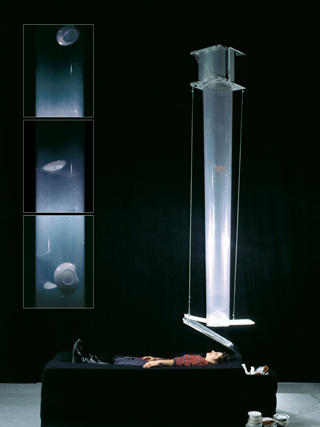

Lawrence Malstaf,

"Territorium", 2010,

Courtesy Fortlaan 17 Gallery.

Lawrence Malstaf,

"Compass", 2005,

Courtesy Fortlaan 17 Gallery.

Lawrence Malstaf,

"Shaft", 2004,

Courtesy Fortlaan 17 Gallery.

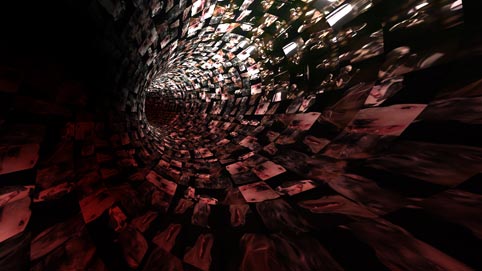

Jean-Michel Bruyère & LFKs, "La dispersion du fils", 2008-2011.

Written for "Digitalarti Mag" and translated by Geoffrey Finch.