N E W M E D I A A R T . E U

> Paris Photo

> Art, technology and AI

> Immersive Art

> Chroniques Biennial

> 7th Elektra Biennial

> 60th Venice Biennial

> Endless Variations

> Multitude & Singularity

> Another perspective

> The Fusion of Possibilities

> Persistence & Exploration

> Image 3.0

> BioMedia

> 59th Venice Biennale

> Decision Making

> Intelligence in art

> Ars Electronica 2021

> Art & NFT

> Metamorphosis

> An atypical year

> Real Feelings

> Signal - Espace(s) Réciproque(s)

> On Combinations at Work

> Human Learning

> Attitudes and forms by women

> Ars Electronica 2019

> 58th Venice Biennale

> Art, Technology and Trends

> Art in Brussels

> Plurality Of Digital Practices

> The Chroniques biennial

> Ars Electronica 2018

> Montreal BIAN 2018

> Art In The Age Of The Internet

> Art Brussels 2018

> At ZKM in Karlsruhe

> Lyon Biennale 2017

> Lyon Biennale 2017

> Ars Electronica 2017

> Digital Media at Fresnoy

> Art Basel 2017

> 57th Venice Biennial

> Art Brussels 2017

> Ars Electronica, bits and atoms

> The BIAN Montreal: Automata

> Japan, art and innovation

> Electronic Superhighway

> Lyon Biennale 2015

> Ars Electronica 2015

> Art Basel 2015

> The WRO Biennale

> The 56th Venice Biennale

> TodaysArt, The Hague, 2014

> Ars Electronica 2014

> Basel - Digital in Art

> The BIAN Montreal: Physical/ity

> Berlin, festivals and galleries

> Unpainted Munich

> Lyon biennial and then

> Ars Electronica, Total Recall

> The 55th Venice Biennale

> The Elektra Festival of Montreal

> Digital practices of contemporary art

> Berlin, arts technologies and events

> Sound Art @ ZKM, MAC & 104

> Ars Electronica 2012

> Panorama, the fourteenth

> International Digital Arts Biennial

> ZKM, Transmediale, Ikeda and Bartholl

> The Gaîté Lyrique - a year already

> TodaysArt, Almost Cinema and STRP

> The Ars Electronica Festival in Linz

> 54th Venice Biennial

> Elektra, Montreal, 2011

> Pixelache, Helsinki, 2011

> Transmediale, Berlin, 2011

> The STRP festival of Eindhoven

> Ars Electronica repairs the world

> Festivals in the Île-de-France

> Trends in Art Today

> Emerging artistic practices

> The Angel of History

> The Lyon Biennial

> Ars Electronica, Human Nature

> The Venice Biennial

> Nemo & Co

> From Karlsruhe to Berlin

> Media Art in London

> Youniverse, the Seville Biennial

> Ars Electronica, a new cultural economy

> Social Networks and Sonic Practices

> Skin, Media and Interfaces

> Sparks, Pixels and Festivals

> Digital Art in Belgium

> Image Territories, The Fresnoy

> Ars Electronica, goodbye privacy

> Digital Art in Montreal

> Art, technology and AI

> Immersive Art

> Chroniques Biennial

> 7th Elektra Biennial

> 60th Venice Biennial

> Endless Variations

> Multitude & Singularity

> Another perspective

> The Fusion of Possibilities

> Persistence & Exploration

> Image 3.0

> BioMedia

> 59th Venice Biennale

> Decision Making

> Intelligence in art

> Ars Electronica 2021

> Art & NFT

> Metamorphosis

> An atypical year

> Real Feelings

> Signal - Espace(s) Réciproque(s)

> On Combinations at Work

> Human Learning

> Attitudes and forms by women

> Ars Electronica 2019

> 58th Venice Biennale

> Art, Technology and Trends

> Art in Brussels

> Plurality Of Digital Practices

> The Chroniques biennial

> Ars Electronica 2018

> Montreal BIAN 2018

> Art In The Age Of The Internet

> Art Brussels 2018

> At ZKM in Karlsruhe

> Lyon Biennale 2017

> Lyon Biennale 2017

> Ars Electronica 2017

> Digital Media at Fresnoy

> Art Basel 2017

> 57th Venice Biennial

> Art Brussels 2017

> Ars Electronica, bits and atoms

> The BIAN Montreal: Automata

> Japan, art and innovation

> Electronic Superhighway

> Lyon Biennale 2015

> Ars Electronica 2015

> Art Basel 2015

> The WRO Biennale

> The 56th Venice Biennale

> TodaysArt, The Hague, 2014

> Ars Electronica 2014

> Basel - Digital in Art

> The BIAN Montreal: Physical/ity

> Berlin, festivals and galleries

> Unpainted Munich

> Lyon biennial and then

> Ars Electronica, Total Recall

> The 55th Venice Biennale

> The Elektra Festival of Montreal

> Digital practices of contemporary art

> Berlin, arts technologies and events

> Sound Art @ ZKM, MAC & 104

> Ars Electronica 2012

> Panorama, the fourteenth

> International Digital Arts Biennial

> ZKM, Transmediale, Ikeda and Bartholl

> The Gaîté Lyrique - a year already

> TodaysArt, Almost Cinema and STRP

> The Ars Electronica Festival in Linz

> 54th Venice Biennial

> Elektra, Montreal, 2011

> Pixelache, Helsinki, 2011

> Transmediale, Berlin, 2011

> The STRP festival of Eindhoven

> Ars Electronica repairs the world

> Festivals in the Île-de-France

> Trends in Art Today

> Emerging artistic practices

> The Angel of History

> The Lyon Biennial

> Ars Electronica, Human Nature

> The Venice Biennial

> Nemo & Co

> From Karlsruhe to Berlin

> Media Art in London

> Youniverse, the Seville Biennial

> Ars Electronica, a new cultural economy

> Social Networks and Sonic Practices

> Skin, Media and Interfaces

> Sparks, Pixels and Festivals

> Digital Art in Belgium

> Image Territories, The Fresnoy

> Ars Electronica, goodbye privacy

> Digital Art in Montreal

> >

THE VENICE BIENNALE

by Dominique Moulon [ September 2009 ]

The 53rd Venice Biennale opened at the beginning of June bringing together artists, curators and critics from around the world before opening to the general public through until November 22nd. On the programme: the “historical” pavilions in the Giardini, collateral events in various places around the city and Daniel Birnbaum’s “Making Worlds” exhibition at the Arsenal.

Steve McQueen,

“Giardini”, 2009.

Shaun Gladwell,

“Interceptor Surf:

Daydream Mine Road”,

2009.

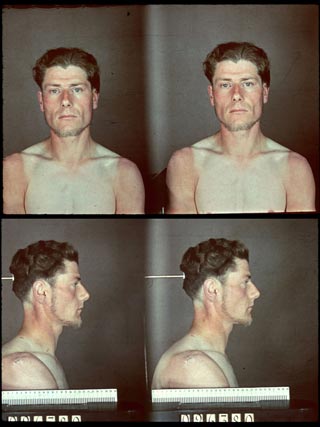

Mark Lewis,

“The Fight”, 2008.

Péter Forgács,

“Col Tempo - The W. Project”,

2009.

Krzysztof Wodiczko,

“Guests”, 2009.

Ragnar Kjartansson,

“The End - Rocky Mountains”, 2009.

Paul Chan,

“Sade for Sade's Sake”,

2008-2009,

© Giorgio Zucchiatti.

John Gerrard,

"Grow Finish Unit",

2008.

Written by Dominique Moulon for "Images Magazine" and translated by Geoffrey Finch for "newmediaart.eu", this article is also available in French on "nouveauxmedias.net".