The organisation of the Biennial of Contemporary Art of Seville was entrusted to Peter Weibel, the director of ZKM in Karlshrue who with the help of Won-il Rhee from Korea, one of the curators of PS1 in New York, and the French director of the FRAC in Orleans, Marie-Ange Brayer, brought together works from nearly a hundred artists, placing the spectator in the centre of their universes.

D

Dozens and dozens of flags placed on the bridge that crosses the Guadalquivir in the direction of the Andalusian Centre for Contemporary Art remind us of the theme of this third edition of the

Seville biennial: Youniverse. Meaning you are at the centre of the universe. But what should we make of the graffiti “YOUPERVER$E”, on the same bridge, twisting its meaning? It is undoubtedly a criticism.

Yaacov Agam,

“Fiat Lux”, 1967.

Interacting

Interacting

I

If there is a notion inherent to the Youniverse exhibition as a whole, it is that of interactivity, which is at the heart of the issue in works such as “Fiat Lux” produced by the Israeli artist Yaacov Agam in 1967. The public is invited to clap their hands to turn on a large light bulb. Let there be light! The organisers are performing a pedagogical act by defining as simply as possible this notion of interaction, which is nonetheless complex, in exhibiting this essentially participative installation that we can today qualify as historic. At a time when homes are equipped with such participative devices, commonly known as “domotics”, the creation date of this work underlines the fact that Op art of the 50’s and 60’s comprises one of the historical anchors for artistic practices associating art with technology that emerged in the following decades. The poetic title of “Fiat Lux” taken from Genesis detracts nothing from the “Readymade” character of this supermarket filament light bulb whose demise is already on the horizon.

Bill Viola,

“The Tree of Knowledge”,

1997, © Giuseppe Martino.

A

Another installation, a little farther away also evokes Genesis. It is called “The Tree of Knowledge” and was conceived in 1997 by the American artist

Bill Viola. The interactivity here is a little more complex because the visitors, by advancing up the corridor that ends in a projected image of a tree, control its growth. Just a sapling to begin with, it grows as they move forward, pushing out leaves, flowers appearing to be replaced by fruit, which then disappear when the tree dies. Stopping in front of this “tree of the knowledge of good and evil” entails stopping the image, hence stopping its growth. It is therefore possible to interrupt our quest by stepping backwards, but who among us is wise enough to give up? Is it not our insatiable curiosity that pushes us to go all the way to the end of this corridor, thereby accepting the consequences? While some are ready to repeat the experience, others have their photo taken beside their trophy without the slightest shame.

Peter Campus,

“Kiva”, 1971,

© Giuseppe Martino.

Entering the image

Entering the image

I

Interactivity cannot be reduced to simply triggering or controlling actions because there are works such as “Kiva” by Peter Campus, that allow us to “enter the image”. This installation dates from 1971 and functions around a closed circuit video device. Two reflective panels of different sizes are attached to the ceiling, directed toward a camera that is set on a monitor. The larger of the two has a hole cut in its centre. Given that the slightest breeze can make them move, they are like mobiles in perpetual rotation. Among the Hopi Indians, the Kiva is a circular room that is half underground with a hole in the ground that enables one to enter into communication with those from “another” time. The device of the American artist meanwhile makes it possible to observe an “augmented” space because the video image in fact takes in the exhibition space, the portrait of the person looking at it and the eye of the camera. The work here then evolves according to its context, as well as to the museum and the spectator with this random element that is inherent in the perpetual movement of the two panels that sometimes or only partially separate us from the camera like the moon sometimes or only partially allows us to perceive the sun.

Masaki Fujihata,

“ Morel´s Panorama”,

2003.

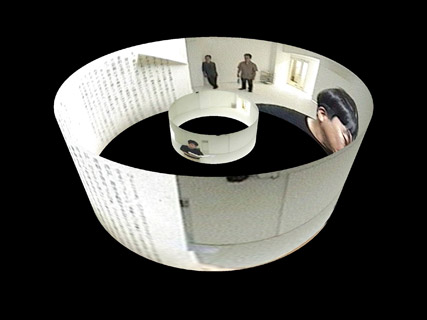

T

The immersive installation of the Japanese

Masaki Fujihata is more recent since “Morel´s Panorama” dates from 2003. In the centre of the room is a camera of which Jean-Louis Boissier says “employs a parabolic mirror by way of a panoramic lens”, before adding: “this camera, whose optical sensor is a mirror is unique in that it throws the point of view out into the virtual and forbids being “behind the camera”.” So no matter what our position is in the space, we enter the image field that covers one of the two virtual cylinders that are being virtually video-projected. All of us are inside as we are outside this panoramic image that is in perpetual agitation to the rhythm of an ambient sound that also seems to move about in space. Then there is this second cylindrical image, likewise covered by a slice of reality where we believe we recognise the artist who is however not in the room. But when he sets the example by encircling the camera with his arms, we imitate him in a desperate attempt to communicate with him. We may know of the narrator’s inability in “Morel’s Invention” written by Adolfo Bioy Casares of making contact with those that surround him, unless it is virtually.

Christa Sommerer

and Laurent Mignonneau,

“Life Writer”, 2006.

Artificial writing

Artificial writing

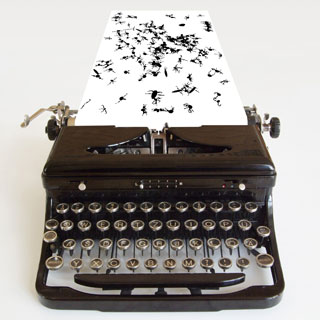

Christa Sommerer

Christa Sommerer is Austrian and

Laurent Mignonneau is French. Since 1991, the two artists have been conceiving interactive creations together such as “Life Writer” in 2006. This involves an old typewriter on which the public is invited to type whose text appears by video projection on a piece of paper that seems entirely normal. But the letters that have been typed by the visitor transform themselves into artificial creatures as soon as the typist activates the carriage return. The typographic characters have thus been converted into genetic algorithms that determine the behaviour of the beasts that scurry about on the paper. Turn the roller toward you and they are crushed by this strange machine; turn it away from you and they are evacuated outside the page. Typing other characters means nourishing them. The speed of their movements when they come to feed upon the typographic energy betrays an apparently insatiable hunger. And like all terrestrial creatures, they end up reproducing themselves to invade the sheet of paper that then proves to be too small!

Robotlab,

“Bios [Bible]”, 2007,

© Giuseppe Martino.

J

Just as there are artists like Sommerer and Mignonneau who question artificial life, there are others like Matthias Gommel, Martina Haitz and Jan Zappe together forming the German collective

Robotlab, who take an interest in the relationship between art and robotics. This group took hold of an industrial robot in 2007 in order to “teach it to write”. So for the past few months, the robot Kuka in the installation “Bios [Bible]” has been copying a bible without interruption that groups the old and new testaments. Equipped with a fountain pen, it is with ink that it is copying the holy scripture in gothic calligraphy, without ever making a mistake or ever forgetting to insert a dropped initial at the beginning of each chapter. It is imperturbable, like a monk in his scriptorium, determined to go to the end of his mission, linking together movements that are stocked in its memory. The columns are 42 lines high, just like the Gutenberg Bible, which announced the end of the era of monk scribes. But how many of these robots are there around the world involved in producing all kinds of objects for our daily lives without us ever seeing a single one? Would we ever see one if artists didn’t show us?

Rafael Lozano–Hemmer,

“Reporters with Borders,

Shadow Box 6”, 2008,

© Antimodular.

Televisual mosaics

Televisual mosaics

T

The Mexican

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer is one of the rare artists to exhibit two works of the series “Shadow Box”. These installations combine cameras, databases and screens. In both cases, the spectator’s silhouette is captured and reveals the contents of the installation. The database of “Third Person”, created in 2006, contains all the verbs of a language, in this case Spanish, conjugated in the third person. So the visitor when they move recognises through their gestures, a multitude of verbs that for some, represent what they are doing. Isn’t this then quite simply the definition of video surveillance cameras that spy and document all our events and gestures in images. As for the database of “Reporters with Borders” created in 2008, it harbours 1600 video sequences representing news reporters from American and Mexican news channels. All of them are stopped, frozen and only begin to move when you approach them as long as they are integrated into the limits of our silhouette, of our field of interest! Which explains the power to hypnotise the chaotic fragmentation of cathode images has.

Shin il Kim,

“Active Anesthesia - the full of square”,

2007 ©, Giuseppe Martino.

T

The luminous installation “Active Anaesthesia”, by the Korean artist Shin il Kim, is just as hypnotising and again proceeds from a form of fragmentation. It is set up in one of the cellars of the Andalusian Centre for Contemporary Art where we discover it off to one side, below a staircase in a setting that is propitious for an intimate aesthetic relationship. The image we see is made up of a mosaic of large sized luminous squares. But the 48 elements that comprise this installation change their luminosity and colours ceaselessly. Something is going on behind what we perceive. So one tries to explore the work by changing one’s point of view. We then discover that these “pixels” are evolving to the rhythm of a televised image that is projected from behind. It is difficult to speak of interactivity here, even though our perception of the work depends entirely on our position in space. We can thus follow the advertising spots of a television channel or prefer to allow ourselves be hypnotised by an abstract geometric painting with changing light. This recalls the work of Jan Dibbets who at the end of the 1960’s transformed televisions into fireplaces broadcasting wood fires with effects just as numbing.

Ruth Schnell,

“Retinal Scripts”,

2005-2008.

Perceiving the invisible

Perceiving the invisible

I

I thought I saw some words floating in space while turning a corner, while turning my head, barely the time it takes to blink. As if the words, or fragments of words were there in suspension, ready to appear under I know not what conditions. A cartel informs me that it is a light installation conceived by Ruth Schnell entitled, “Retinal Scripts”. The Austrian artist has in fact placed vertical bars in different locations around the exhibition whose electro-luminescent lighting diodes are controlled digitally through high frequency pulses. It is in this way that the lit characters forming words or word fragments furtively imprint themselves on the visitors’ retinas when they make involuntary movements to glance at something. And the pleasure of being surprised by these poetic flashes when you least expect them is equal to the difficulty of trying to voluntarily make them appear in an attempt to perceive the invisible by energetically turning one’s head.

Informationlab

“Cell Phone Disco”,

2007.

T

There are a lot of museums where the use of mobile telephones is disdained. In one of the rooms of the Andalusian Centre for Contemporary Art on the other hand, it is required. The room is one in which the installation “Cell Phone Disco”, created in 2007 by Auke Touwslager and Ursula Lavrencic, members of the

Informationlab collective based in Amsterdam is installed. The work is made up of thousands of red electroluminescent diodes that are sensitive to the electromagnetic radiation transmitted by an active mobile telephone. Calling or receiving a call makes it possible then to observe the invisible forces that we generate when we make a call. The two artists make no judgements about the microwaves that are part and parcel of mobile telephones, but they draw our attention to the mysterious invisible electromagnetic fields that surround us, as much in nature as they do in urban environments. They have nonetheless chosen to reveal the invisible with the colour red, which often signals danger.

Electronic Shadow

“Ex-îles”, 2003.

Crossings and trajectories

Crossings and trajectories

T

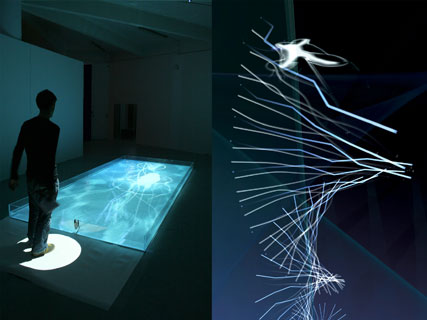

There are also in this exhibition, a few collectives and other French artists like

Electronic Shadow formed in 2000 by Naziha Mestaoui and Yacine Aït Kaci who propose linking the real space of the exhibition with the immaterial space of the Internet. The water in the basin of the installation “Ex-île” seems to extend into the reflection of the projected image while the visitor is drawn by a circle of white light that pulses on the ground. Entering into the light means triggering a white silhouette that crosses the image swimming the length of the very real water of the basin. And then there is this threadlike image that looks like a strand of DNA that little by little fills in the trajectories described by the swimmer. But the filamentous structure that is being built before our eyes is none other than the fruit of a collaboration between strangers because it is also possible to participate in the experiment by entering the white circle that dances on the screen of the Internet page, extending the installation of the exhibition into the virtual.

Roland Baladi,

“Tracing EURABIA by a flight between cultures”,

2008.

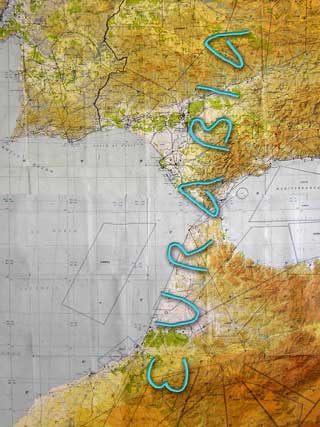

L

Lastly, Peter Webel is behind the video installation “Tracing EURABIA by a Flight Between Cultures” by the French artist

Roland Baladi. This piece groups seven screens each presenting an aerial view where the camera slowly moves over the landscapes that follow one upon the other. At times an expanse of water fills the entire space of one of the screens at the centre of the piece. The key to this image enigma is found in the imposing catalogue of the “Youniverse” exhibition where we discover the map of the seven trajectories, or seven low altitude flights and the seven letters of the alphabet E, U, R, A, B, I, A. The first letter is rooted in the Moroccan Atlas Mountains while the last ends over the mountains of the Spanish Sierra Morena. But what is the message of this celestial acronym if it is not the geographic necessity for an expanding Europe to open up to the Arab world that occupies the other shores of a shared sea? Seville and Andalusia are already familiar with the riches that are born of the hybridisation of cultures.

Written by Dominique Moulon for "Images Magazine" and translated by Geoffrey Finch for "newmediaart.eu", this article is also available in French on "nouveauxmedias.net".

![Bios [Bible]](youni_IM/youni_06.jpg)